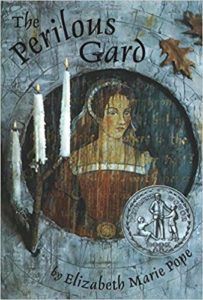

In 1550s England, Kate Sutton and her sister Alicia are ladies-in-waiting for Elizabeth I during the reign of Elizabeth’s sister Mary, Queen of Scots. After Alicia writes an inflammatory note to Queen Mary, Kate takes the blame and is exiled to an isolated castle, or gard, known as Elvenwood Hall. The lord of the house, Sir Geoffrey Heron, is distraught because his young daughter, Cecily, has just gone missing. Sir Geoffrey believes that his younger brother, Christopher, is responsible. Of course, everything is more complicated than it initially appears. The villagers tell rumors about the Fairy Folk, mysterious, proud people who live underground in a stone fortress near the castle. They supposedly observe strange rituals, including an annual human sacrifice at All Hallows Eve. This is a teind, or a payment to hell. Trying to save herself and others, Kate gets caught up in the sinister, intriguing world of the Fairy Folk and their leader, the Lady in Green. My adult life experiences and knowledge of mental health help me to appreciate the characters’ psychological depth. Kate describes “the Weight,” the horrifying sensation that results from living in the Fairy Folk’s subterranean lair: “The agonized horror she felt now was of the reality of the Hill itself—the tons and tons of actual earth and stone lying above her, closing down on her, shutting her in. It was like some suffocating dream of being buried alive; or rather it was like the moment of awakening from that dream to find that it was true (160).” At 11 or 12, I identified this as a description of claustrophobia. This is true, but as an adult, I also recognize the general symptoms of anxiety or a panic attack, regardless of the cause. When Kate is betrayed, she describes the nightmarish feeling of familiar, mundane objects suddenly seeming unfamiliar and threatening. Years later, in college, I’d read Freud describe the blurring between threatening and unthreatening places and objects in his essay “The Uncanny.” First encountering complex psychological phenomena in a YA novel made them relatable and clear to me. Kate is a courageous, resourceful heroine. She subverts the “damsel in distress” trope by rescuing the hero. I’ve always admired Kate’s strong will. Although Kate fears the Fairy Folk, she also admires their adherence to traditions. The Lady in Green offers her human captives drugs to numb the horror of the Weight. Kate is the only one who refuses. Near the end of the book, when the Lady offers Kate a love potion, she refuses that as well. At the time, I thought that love potions—if they existed—would be like placebos. Implicitly, this taught me something about agency and consent. I realized that even if it were possible to make someone fall in lust or love with you, it would be unethical. Studying literature helped me to put The Perilous Gard in its cultural and historical context and appreciate it on deeper levels. The novel is a retelling of the ancient Scottish myth of Tam Lin and other stories about the teind. When I first read it, I assumed that the Fairy Folk were the last holdouts of an ancient religion. Christian authorities literally and figuratively demonized them and drove them underground. That’s one interpretation, but the book hints that the Fairy Folk might actually be immortal and supernatural. They’re not just followers of a pagan religion: they’re so ancient that these religions are about them. Reading Celtic and other European myths about the Faerie and their interactions with humans enriches my enjoyment of The Perilous Gard. I notice new details in it, year after year. See also: 100 Must-Read YA Historical Novels